Emerging Markets: A Letter from Manila

14 October 2024

Here our specialist Emerging Markets Equities investment partner, Northcape Capital, shares with us their observations into the Philippines following a recent research trip. The team shares their insights from meetings on the ground, and why they are optimistic that the current political environment can help drive improved shareholder returns which could be a potential valuation re-rating catalyst for the market.

This information has been prepared by Northcape Capital, the underlying investment manager for the Warakirri Global Emerging Markets Fund.

The Philippines – A Poster Child Emerging Market

The air is hot and humid. The gentle perfume of tropical fruits wafts up to a pedestrian walkway which connects a new five-star hotel to luxury boutiques on the other side of a wide boulevard (Exhibit 1). Sleek office towers reflect the afternoon sunlight whilst a group of affluent-looking Koreans walks past carrying shopping bags labelled “Gucci”.

You would be forgiven for thinking the scene described is Orchard Road, Singapore but in fact the author is in downtown Manila, and the signs of growing wealth all around are representative of a country which may finally be entering an extended golden period after many false starts.

Prima facie the Philippines is in many ways the poster child Emerging Market. The country has a population of 116 million that is growing at 1.5% per annum (double the rate of even India’s population growth) thanks to a fertility rate of 2.75, which is amongst the highest in EM. The population is exceptionally young, with a median age of just 25.7 – by comparison to India, which is typically and correctly, praised for having strong demographic tailwinds, with a median age of 28.4.

Exhibit 1: Downtown Makati, Manila, the Philippines

Source: Northcape Capital

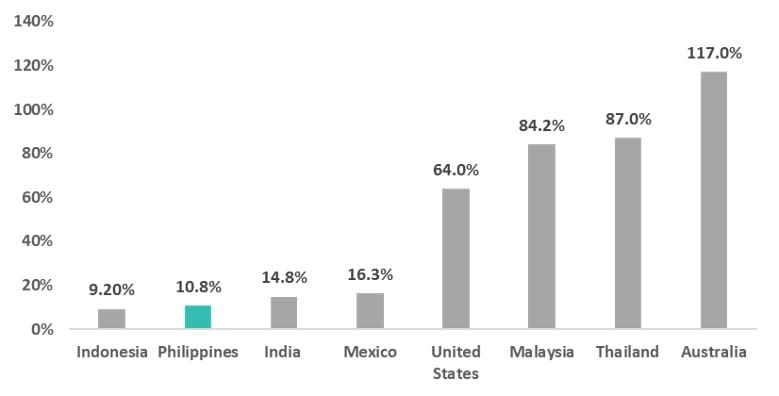

By comparison to its Southeast Asian neighbours, the Philippines remains on average a poor country with plenty of opportunity for catch up growth. GDP per capita is just US$3,498 – well below that of Indonesia (US$4,788), Malaysia (US$11,933) and even frontier market Vietnam (US$4,168). The country is still in the nascent stages of financial development, with low debt levels, and less than half of the population having a bank account. Total private debt at 48% of GDP is amongst the lowest in EM, as is consumer debt (Exhibit 2).

In a world with too much debt and demographic headwinds, the Philippines is a clear standout, but the country also wins in a world where trade in goods has likely already peaked, and globalisation is in retreat. The reason is that, unlike most EM peers, the Philippines is a net importer of goods. To an extent almost unrivalled in the EM index, the country’s economy is driven by the stable engine of domestic consumption, resilient to trade shocks and global economic conditions.

Exhibit 2: Consumer Debt to GDP %, Selected Countries

Source: CEIC

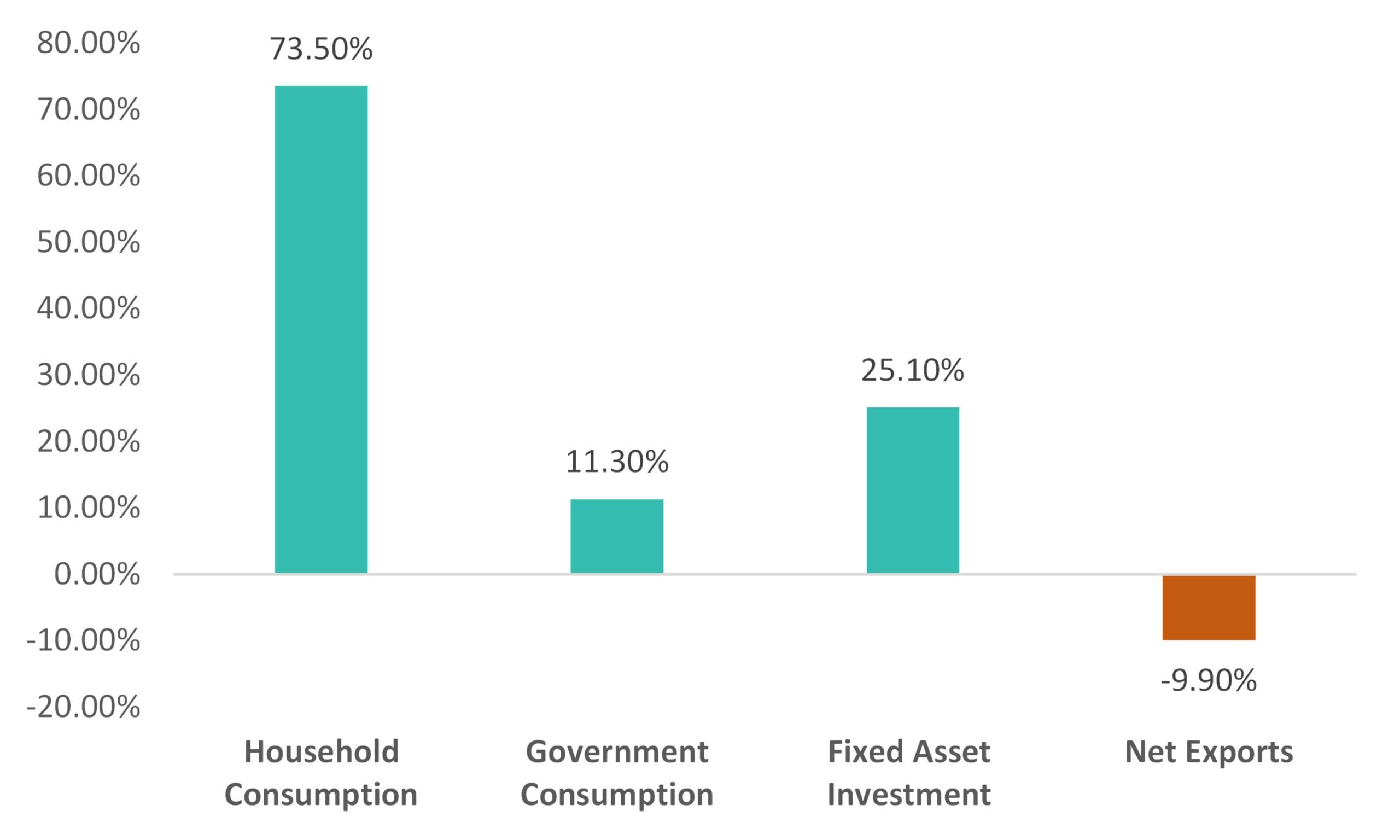

As Exhibit 3 shows, household consumption accounts for a mighty 74% of GDP. The Philippines differs from the typical EM economy in another important sense: the service sector is by far the biggest sector of the economy. Whilst agriculture contributes less than 10% of GDP and industry significantly less than a third, the service sector makes up 60% of the country’s economic output.

The country’s strength in services is reflected in its number 1 position globally in Business Process Outsourcing (BPO), and in remittances which, at 9% of GDP, is the highest as a share of the economy for any country in the EM index. Whilst the outlook for remittances is generally considered to be positive given global demographic changes (more than 70% of Filipinas working overseas are employed in childcare, aged care and general home care), there are some concerns emerging about the potential negative impact of Artificial Intelligence (AI) on the BPO industry.

Whilst in Manila, your correspondent discussed the latter with the legendary Jack Madrid, President of the IT & Business Process Association of the Philippines (IBPAP). Madrid noted that although generative AI is yet to have much impact on the BPO job market, in the longer term it could “potentially displace certain tasks”. Whilst the full impact of AI is impossible to accurately predict at this stage, Mr Madrid notes that the primary reason for the Philippines’ success in BPO – in addition to the high level of English in the country – is “empathy”, with Filipino call centre workers excelling at this relative to competing countries. Since callers are often frustrated and impatient, this is a valuable trait, which may also explain the country’s strong output of high-quality nurses.

On a related note, Mr Madrid also notes that the largest sector in the Philippines BPO sector is now healthcare, which often requires staff to have medical qualifications, such as a nursing degree. The caller may be an elderly patient in Florida enquiring about interactions between medicines or a young working mother in Arizona asking for advice about her child’s minor health issue. For a number of reasons – not least legal liability – this aspect of BPO is unlikely to be replaced by AI any time soon.

The composition of the Philippines economy has not changed significantly in recent years so this is not the origin of the notable current optimism on the ground in the country. To understand that we need to look to the 2022 presidential election.

Exhibit 3: Components of the Philippines’ GDP

Source: CIA World Factbook

Optimism on the ground

Bongbong Marcos assumed office on 30 June 2022, and represented a major change from his predecessor, the erratic and controversial Rodrigo Duterte. Perhaps surprisingly for those familiar with the authoritarian rule of his father – who ruled the country under martial law for decades – Marcos Jr represents a return to a degree of normalcy following the chaos of the Duterte presidency, particularly in two key areas: foreign policy and attitude towards business.

On foreign policy, Duterte pursued a closer relationship with China (and, to a lesser extent, Russia) at the expense of the Philippines’ relationship with the United States. In hindsight, this proved to be a spectacularly misguided policy. In the words of Joshua Kurlantzick at the Council on Foreign Relations, “Duterte received many commitments from Beijing and some infrastructure investment, but ultimately — as COVID hit, China’s economy slowed, Beijing revamped the Belt and Road Initiative, and…a lot of the promised aid and investment never came to pass”.

Exhibit 4: Manila skyline

Source: Northcape Capital

Strengthening US Relations

Marcos has pivoted away from China and tried to repair relations with the United States. Last year he opened up access to almost double the number of the Philippine military bases for the U.S. and made headlines when he went much further than any regional leader – even U.S. officials – in congratulating the winning Democratic Progressive Party in Taiwan. Foreign policy experts noted that his statement was far stronger than those of other Southeast Asian countries with close informal links to Taiwan, like Singapore. Marcos Jr. is betting that pivoting back to the US will pave the way for more FDI into the country and will repair the stock market de-rating that occurred under Duterte (see Exhibit 6).

Exhibit 5: Marcos Jr. has been focused on repairing relations with the U.S.

Source: Reuters

Also key to Marcos Jr’s administrative agenda is a return to the pro-business landscape that the Philippines enjoyed under the Noynoy Aquino administration – a period during which the country’s stock market was the single best performer in the entire EM index – in contrast to the almost overtly anti-business policies that Duterte enacted.

First, Marcos Jr’s pick for central bank governor – Eli Remolona – was a clear message that independence of the country’s central bank (Bangko Sentral ng Philipinas, or BSP) is sacred with decision making the sole responsibility of internationally recognised economists and not political cronies (as the Philippines has sometimes had in the past). Remolona worked for 14 years at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York and for 19 years at the Bank for International Settlements (BIS), where he was regional head for Asia and the Pacific from 2008 to 2018.

Exhibit 6: The Philippines stock market de-rated to discount valuations under Duterte

Source: CLSA

He was an editor of the BIS Quarterly Review and was an associate editor for finance of the International Journal of Central Banking, as of 2005, making him one of the most highly qualified EM central bankers.

The author spent an afternoon at the BSP engaged in various meetings, including one with Remolona’s deputy, and came away very impressed with the depth of the talent in the organisation (see Exhibit 7).

Exhibit 7: The author in the lobby of the BSP – the Philippines’ Central Bank

Source: Northcape Capital

On the private sector, Marcos Jr’s first focus was the energy sector, which Dereck Aw of Control Risks noted “had resembled a squabbling schoolyard…prior to the change in government”.

Raphael Lotilla, Marcos’s handpicked green energy czar, introduced a policy encouraging wide-ranging foreign involvement in renewables, implementation of a competitive green energy bidding process and rollout of an ambitious Philippine Offshore Wind Roadmap, which has identified 178 GW of technical potential in total.

Similarly, the domestic mining sector, previously hindered by excessive domestic protectionism and foreign ownership restrictions, is finally able to court international investors and tap into surging global demand for nickel, copper and gold, of which the Philippines boasts among the world’s largest proven reserves.

Other policy changes, whilst modest, have been pragmatic and well received: an excise tax on single-use plastics, a value-added tax (VAT) on digital services and reforms on pensions and government procurement.

Going forward, Marcos will likely continue to encourage foreign direct investment (FDI) through his dual approach of friendlier relations with the West (in particular, the U.S.) and removing red tape and protectionist regulations. This should bode well not just for the economy, but also for the local share market which – at around 10x forward earnings – is cheap both compared to history and relative to the rosy outlook for corporate profits.

The next presidential election is not until 2028 but next year the country will face mid-term elections, where key legislative and local positions will be selected by voters. Expert opinion seems to be aligned that the mid-terms are unlikely to derail the two key foundations of the Marcos administration: a pivot back to stronger relations with the US and a return to overtly pro-business policy making.

Dereck Aw of Control risks summarizes the situation facing the country succinctly:

“While the stability and practicality promised by [Marcos Jr’s] leadership are undeniable, the effectiveness of his policies and feasibility of his vision at such a crucial time will ultimately determine if the Philippines can emerge as a pivotal regional player or remain entrenched in the same old challenges of the past”.

In conclusion, we are optimistic that the Philippine’s current political regime can help drive improved shareholder returns which could be a potential valuation re-rating catalyst for the market.

For more information, please contact us on 1300 927 254 or visit Warakirri Global Emerging Markets Fund.

The information in this document is published by Warakirri Asset Management Limited ABN 33 057 529 370 (Warakirri) AFSL 246782 and issued by Northcape Capital ABN 53 106 390 247 AFSL 281767 (Northcape) representing the Northcape’s view on a number of economic and market topics as at the date of this report. Any economic and market forecasts presented herein is for informational purposes as at the date of this report. There can be no assurance the forecast can be achieved. Furthermore, the information in this publication should only be used as general information and should not be taken as personal financial, economic, legal, accounting, or tax advice or recommendation as it does not take into account an individual’s objectives, personal financial situation or needs. You should form your own opinion on the information, and whether the information is suitable for your (or your clients) individual needs and aims as an investor. While the information in this publication has been prepared with all reasonable care, Warakirri and Northcape do not accept any responsibility or liability for any errors, omissions or misstatements however caused.