Emerging Markets: China – a "Least Preferred" sovereign

12 June 2024

China’s investment-led growth model has remained largely unchanged for the past three decades. This model emphasises economic expansion through investments in real estate, infrastructure, and manufacturing capacity, guided by state directives. The Chinese economy remains highly indebted and accordingly, and for other reasons discussed in this paper, China remains a “Least Preferred” sovereign.

This information has been prepared by Northcape Capital, the underlying investment manager for the Warakirri Global Emerging Markets Fund.

China’s investment-led growth model has remained largely unchanged for the past three decades. This model emphasises economic expansion through investments in real estate, infrastructure, and manufacturing capacity, guided by state directives. It involves state-controlled bank lending, substantial local government subsidies for favoured industries, and direct investment in infrastructure – primarily through Local Government Financing Vehicles (LGFVs).

The government has de-emphasised the development of a social safety net and public healthcare. This combined with stagnant wage growth and financial repression of individual savers (reflected in low deposit rates), has seen consumers focus on saving. Consequently, China’s household consumption has remained low, with a correspondingly high savings rates as a percentage of GDP.

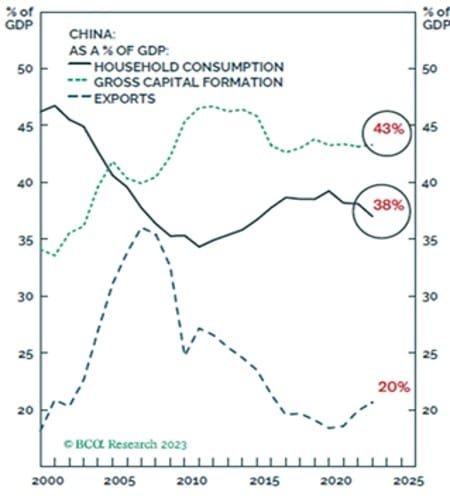

The persistently high levels of fixed asset investment and low consumption as a share of GDP are the enduring features of China’s economic model as shown in Exhibit 1.

Exhibit 1: China Consumption and Capital Formation as a % of GDP

Source: BCA

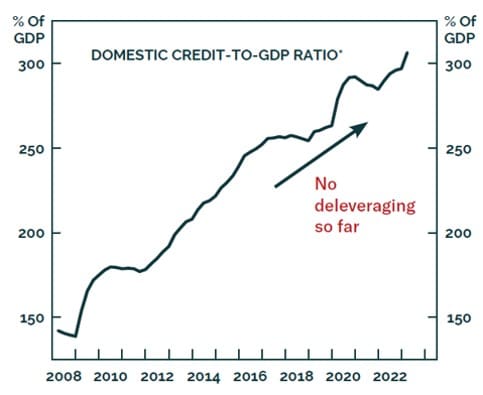

While this emphasis on developing fixed assets was rational in the 1990s and 2000s, in recent years, particularly from around 2010, there has been diminishing returns on investment. The escalating debt-to-GDP ratio and growing gap between GDP and debt growth since 2010 (shown in Exhibit 2) highlights this declining productivity of debt and widespread capital misallocation.

Exhibit 2: China’s rapidly increasing Debt to GDP ratio

Source: BCA

Despite the overall continuity of this economic model, China’s economy has faced two significant policy-induced shocks over the past three years, exposing vulnerabilities to its investment-led growth approach:

1. The Central Government’s “COVID-Zero” Policy:

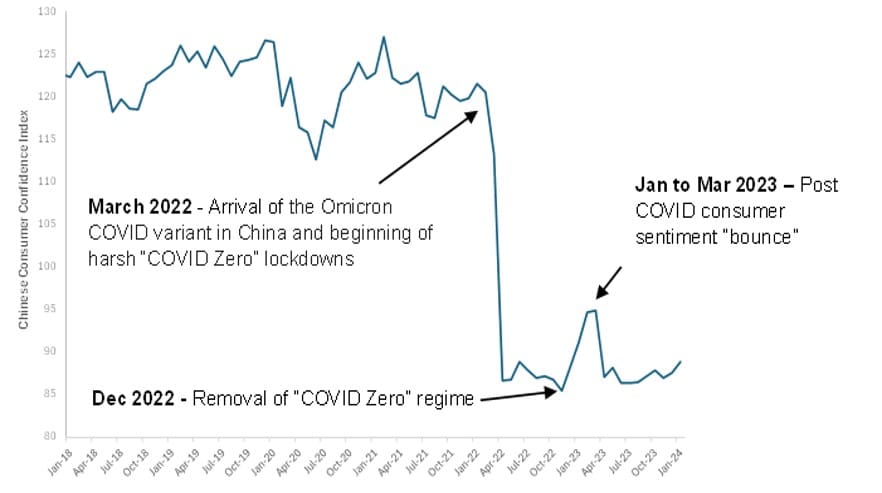

China’s rigorous “COVID-Zero” policy led to drastic measures such as stringent lockdowns, extensive testing, and forced quarantine, causing significant distress among the populace. The sudden policy reversal in November 2022 amid rising social discontent, coupled with the government’s unpreparedness to handle the ensuing COVID outbreak, strained public trust in the Communist Party’s governance.

2. The Government’s “Three Red Lines” Policy:

Introduced as the economy rebounded from the initial COVID lockdowns in August 2020, the “Three Red Lines” policy aimed to rein in investment in the real estate sector to mitigate financial risks and enhance affordability. Subsequently, the crackdown extended to internet and education companies, the former including fintech and gaming, under the pretext of curbing “capital expansion disorderliness” but was aimed at the government retaking control of these sectors given their ability to influence the populace.

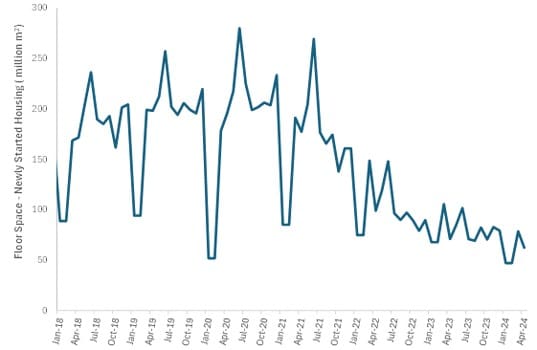

These policy measures have severely dampened consumer sentiment (see Exhibit 3), leading to a decline in consumer spending across various sectors. Weak consumer sentiment has also fed into property sales, which precipitated the bankruptcy of many over indebted developers (Country Garden and Evergrande being the most conspicuous examples). Given the downward spiral in confidence, total residential floor space sold in China has declined 60-70% from the 2020 peak. Consumer confidence in the property sector will be very difficult for the government to turn around given the massive inventory of completed and half-finished apartments (estimated to be in the order of 100m units!, as shown in Exhibit 4).

Exhibit 3: China’s Consumer Confidence Index – 2018 to Present

Source: NBS

This has profound ramifications, given the property sector’s substantial contribution to GDP (the IMF has estimated that at its peak real estate accounted for 20% of GDP). To date there have been no signs that the decline in housing starts has bottomed. Despite a significant drop in residential property starts, real estate construction activities have only seen relatively modest declines to date, down 7-10% in 2023, fueled by the backlog of presold but unfinished apartments. Concerns over social stability have prompted the government to enact policies to prop up the property sector.

Exhibit 4: China Floor Space of Newly Started Housing – 2018 to Present

Source: NBS

This concern culminated in the government announcing in May 2024 a RMB 300m (~US$41 billion) funding package to buy finished apartments (with the goal of putting a floor under apartment prices) as well as to facilitate the completion of unfinished apartments. This package however is woefully inadequate to stop the decline in Chinese property prices and turn around confidence in our view. It represents a mere 15% of the apartments that have been completed but are already on the market for sale and 1-2% of the total volume of uncompleted apartments.

The decline in the property market therefore poses a significant medium-term challenge to China’s investment-driven economic model. In response, the government has thus far not looked to change the economic growth engine to consumption but instead has doubled down in maintaining high investment levels, particularly in new manufacturing capacity.

Investment has shifted towards strategic industries such as electric vehicles, renewable energy, and semiconductors, fostering a surge in production capacity in these areas.

We do not see this shift towards manufacturing as a fundamental shift in China’s investment led economic model and it is almost certain to produce overcapacity and very low returns on investment. We therefore expect to see a continuation of rising debt levels, low levels of consumption as a share of GDP, and a continued high savings rate going forward.

We fully expect Chinese economic growth to fall further over the medium term as the country continues to misallocate capital in Great Wall proportions.

Compounding this issue is the demographic timebomb the country is facing, with a declining population being a long term drag on growth.

We therefore expect the Chinese domestic economy to become less important as a source of demand for capital goods. This will have a material impact on capital good exporters such as Japan and Germany (China is 7% of total German exports), and commodity exporters.

As we have previously noted, the full impact of the decline in the Chinese property market has not yet fully fed through into a decline in construction activity. When this occurs, we see a high risk of a large decline in demand for industrial metals and in particular steel. We may also see a rolling off in the investment in the Chinese manufacturing sector at some point soon. Although the timing of such events is hard to predict.

China is likely to remain a key global manufacturing hub for some time, however we anticipate rising protectionism will crimp the ability of China to continue to grow exports (we explore this more fully in the next section). This will benefit countries that do not face similar trade barriers and can compete as alternative sources of manufactured goods (Mexico, Vietnam etc.) as well as countries with large domestic markets that can benefit from manufacturing being on-shored (US and India). We expect these regions to be key drivers of global growth over the medium-term.

China’s overcapacity in many industries has driven fierce discounting in global markets as its exporters try to win global share for their products. The result has been that it has not only been exporting goods but also deflation. Growing protectionism is likely to reduce these global deflationary pressures.

Weak domestic Chinese demand has not been able to absorb the additional production in key strategic industries such as EVs and renewables. It is therefore not a surprise that we have seen a surge in Chinese exports over the last 24 months in these industrial goods and autos.

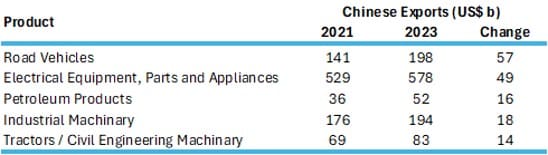

Exhibit 5 highlights the key changes in Chinese exports between 2021 and 2023. As can be seen, the vehicles and electrical equipment are by far the largest product groups that have seen an increase in exports. We note that following the COVID “work-from-home” boom, China’s computer producers have seen a steep decline in exports offsetting a large part of these gains.

With rising protectionist sentiment in the US, Europe and other countries, there is significant risk that Chinese exporters will see further trade barriers for their major industrial and auto exports.

Exhibit 5: Largest increases in Chinese exports between 2021 and 2023

Source: GAC

For example, in October 2023 an EU investigation found “sufficient evidence tending to show that imports of electric cars concerned from the People’s Republic of China are being subsidised.” It appears it is only a matter of time before the EU imposes tariffs on Chinese autos. Similarly, over the last six months, Brazil has opened probes into the alleged dumping of industrial products by China on products ranging from metal sheets and pre-painted steel to chemicals and tyres.

The major growth markets such as Russia, ASEAN, the Middle East and Africa are also relatively small markets compared to the EU or the US. The ability of these markets to continue to absorb more and more Chinese exports is therefore questionable. Hence, we do not see the recent surge in Chinese exports as a sustainable growth driver for China’s economy and expect growth in Chinese exports to slow soon.

While the government targets 5% growth in 2024 through continued infrastructure and industrial investments, this approach merely delays addressing the key structural issues. Over the medium to long term, the risk of stagnation and “Japanification” looms large, reflecting systemic misallocation of capital and the government’s reluctance to reform the economic model.

We are already seeing disinflation creeping into the economy and consumer sentiment has not improved. Without a change in policy direction this is a recipe for consumer retrenchment (and high savings), low and declining profitability, and firms struggling with high debt loads.

We therefore expect to see corporate debt levels continue to increase as well as a continuation of a high savings rate. In this scenario, China’s medium-term economic growth will continue to slow.

For more information, please contact us on 1300 927 254 or visit the Warakirri Global Emerging Markets Fund page.

The information in this document is issued by Warakirri Asset Management Limited ABN 33 057 529 370 (Warakirri) AFSL 246782 and Northcape Capital ABN 53 106 390 247 AFSL 281767 (Northcape) representing the Northcape’s view on a number of economic and market topics as at the date of this report. Any economic and market forecasts presented herein is for informational purposes as at the date of this report. There can be no assurance the forecast can be achieved. Furthermore, the information in this publication should only be used as general information and should not be taken as personal financial, economic, legal, accounting, or tax advice or recommendation as it does not take into account an individual’s objectives, personal financial situation or needs. Investors should not rely on the information in this document without first referring to the Warakirri Global Emerging Markets Fund’s Product Disclosure Statement (PDS), Additional Information Booklet and Target Market Determination (TMD) and seeking independent advice from their financial adviser. A PDS for the Fund is available at www.warakirri.com.au or by calling 1300 927 254. The PDS should be considered before making an investment decision. Investments entail risks, the value of investments can go down as well as up and investors should be aware they might not get back the full value invested. Portfolio holdings are subject to change. You should form your own opinion on the information, and whether the information is suitable for your (or your clients) individual needs and aims as an investor. While the information in this publication has been prepared with all reasonable care, Warakirri and Northcape do not accept any responsibility or liability for any errors, omissions or misstatements however caused.